Hunter-gatherer childhoods are more natural and adaptive

The study, published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, argues that hunter-gatherer childhoods may offer clues to the conditions that children are psychologically adapted to, since humans lived as hunter-gatherers for 95% of our evolutionary history. The authors, Dr Nikhil Chaudhary, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Cambridge, and Dr Annie Swanepoel, a child psychiatrist, call for new research into child mental health in hunter-gatherer societies.

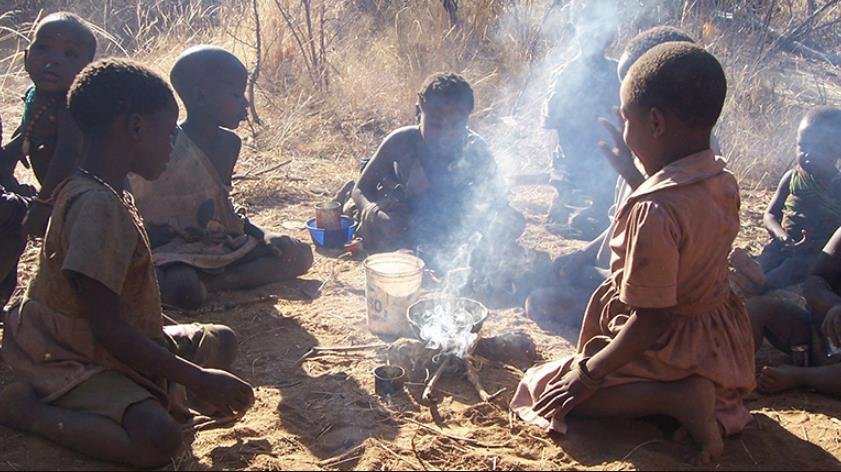

They point out that hunter-gatherer children live in very different environments and circumstances than those in developed countries, and that they face many difficulties that are not experienced in the modern world. However, they also highlight some major differences in the ways that hunter-gatherer children are cared for, which could have positive implications for their development and well-being.

Physical contact and attentiveness are key to infant care

One of the differences is the high level of physical contact and attentiveness that hunter-gatherer infants receive from their caregivers. The study cites the example of the !Kung people in Botswana, who keep their infants in physical contact with someone for around 90% of daylight hours, and respond to almost 100% of their crying bouts with comforting or nursing. Scolding is extremely rare among hunter-gatherer caregivers, who are usually very gentle and patient with their infants.

The study suggests that this kind of attentive childcare is made possible by the major role played by non-parental caregivers, or alloparents, who provide almost half of the child’s care in many hunter-gatherer societies. Alloparents include older siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, and even unrelated adults who are part of the community. They help share the burden of childcare and provide a variety of social and emotional support to the child.

Children learn through play and exploration

Another difference is the way that hunter-gatherer children learn and acquire skills. The study notes that hunter-gatherer children are not formally taught by their elders, but rather learn through play and exploration, often in mixed-age groups. They have a lot of autonomy and freedom to choose their own activities and pace of learning, and they are rarely coerced or punished for their mistakes.

The study argues that this kind of self-directed learning is more natural and adaptive for human children, who have evolved to be curious and creative. It also suggests that hunter-gatherer children develop a sense of competence and confidence, as well as social and emotional skills, through their playful interactions with their peers and the environment.

Hunter-gatherer parenting could inspire new interventions

The study concludes that paying greater attention to hunter-gatherer childhoods could help economically developed countries improve education and well-being for their children. It proposes that some aspects of hunter-gatherer parenting, such as increased physical contact, alloparenting, and self-directed learning, could be incorporated into experimental intervention trials in homes, schools, and nurseries.

The authors acknowledge that there are many challenges and limitations to applying hunter-gatherer parenting practices in the modern world, and that more research is needed to understand the effects and feasibility of such interventions. They also stress that hunter-gatherer childhoods should not be idealised, and that they are not a model for how all children should be raised. Rather, they are a source of inspiration and insight into the diversity and adaptability of human childhoods.